Practitioner Note

One of the most common moments before a technology failure is not a crisis meeting or a missed deadline. It’s a status update.

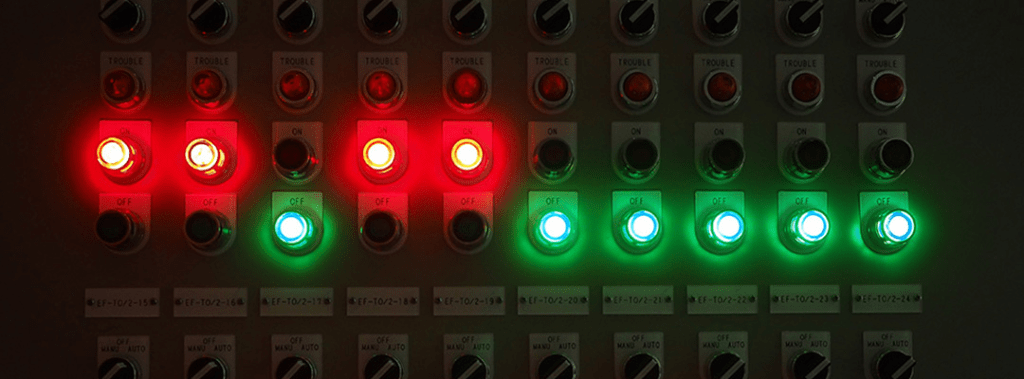

The dashboard is green. Milestones are technically met. Deliverables are checked off. From the outside, the project looks healthy. Inside, almost everyone involved knows something is wrong—but no one can quite name it in a way that changes direction.

This is the point where many failures become inevitable.

The signal people learn to ignore

In real-world projects, failure rarely announces itself loudly. It shows up as small, persistent signals:

- Teams stop asking “why” and focus only on “when”

- Meetings become about defending progress instead of discussing outcomes

- Risks are logged but never escalated

- User feedback is acknowledged, then deferred indefinitely

- Everyone agrees something feels off, but no one owns the feeling

These are not technical issues. They are early warnings that decision-making has narrowed.

The system hasn’t failed yet—but the ability to correct course has.

How incentives quietly override judgment

One pattern that appears again and again is incentive misalignment masquerading as momentum.

By the time a project reaches a visible stage:

- Leaders are invested reputationally

- Teams are invested professionally

- Vendors are invested contractually

- Timelines are politically sensitive

At that point, stopping or revising the effort feels riskier than continuing, even when evidence suggests otherwise. The organization starts optimizing for not being the person who slows things down.

This is how projects drift from “does this work?” to “can we say it worked?”

Why expertise doesn’t prevent this

It’s tempting to believe that better talent or more experience prevents these outcomes. In practice, the opposite is often true.

Highly experienced teams are:

- Better at working around constraints

- Better at producing acceptable outputs under pressure

- Better at rationalizing tradeoffs after the fact

Competence can mask structural flaws longer. Skilled professionals keep systems operational even as strategic misalignment grows. By the time failure is undeniable, reversal is no longer politically or operationally feasible.

The tools still work. The people are still capable. The decision space has simply collapsed.

The moment that matters most—and is least visible

The most important moment in many projects happens quietly, often early:

When someone realizes the original assumptions no longer hold.

This might be:

- A change in leadership priorities

- A shift in user needs

- New regulatory pressure

- Budget constraints that alter scope

- Evidence that adoption will be far lower than expected

In healthy systems, this realization triggers reassessment. In fragile ones, it triggers silence.

People wait for someone else to raise the concern. Over time, the concern becomes harder to articulate without sounding obstructive. Eventually, it disappears from the conversation entirely.

That’s not because it was resolved—but because it became unsayable.

What practitioners often wish they could say

Across roles and sectors, practitioners tend to share the same private thoughts:

- “This solves a different problem than the one we’re measured on.”

- “We’re optimizing the metric, not the outcome.”

- “This made sense six months ago, not now.”

- “No one is empowered to change this anymore.”

- “We’re too far in to admit the assumptions were wrong.”

These are not complaints. They are diagnostic statements. But without a structure that invites them into decision-making, they remain hallway conversations.

A small but meaningful difference

In the projects that don’t fail this way, one thing is usually present:

A designated point where reassessment is not only allowed, but expected.

Not a post-mortem. Not a retrospective after delivery. A real checkpoint where someone has the authority—and psychological safety—to ask:

“If we were deciding today, would we still do this the same way?”

That question doesn’t guarantee success. But its absence almost guarantees failure.

The quiet takeaway

Most technology failures aren’t caused by incompetence, bad tools, or even poor intentions. They happen when systems become very good at moving forward and very bad at stopping.

From the inside, failure often looks like professionalism, progress, and patience—right up until it doesn’t.

Practitioners usually see this coming. The challenge is not insight. It’s whether the system allows insight to matter before it’s too late.

Leave a comment